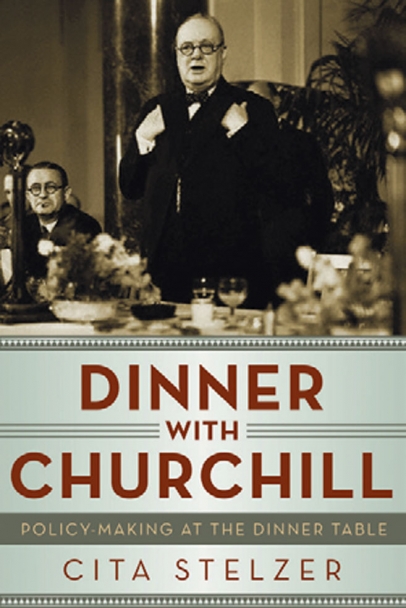

Dinner with Churchill

Dinner with Churchill: Policy-Making at the Dinner Table

by Cita Stelzer

In 1931, during the dark days of Prohibition, Winston Churchill was hit by a car. He asked the attending physician to write the following note, which he knew he would need in those dry days.

“This is to certify that the post-accident convalescence of the Hon. Winston S. Churchill necessitates the use of alcoholic spirits especially during meal times. The quantity is naturally indefinite but the minimum requirements would be 250 cubic centimetres.”

There are conflicting stories about whether Churchill was actually a heavy drinker. He always seemed to have a drink in hand, but those who knew him well say he watered down his whiskey until it tasted like “mouthwash” and that he was never worse for the wear while drinking.

This well-researched and charming book examines the gastronomic pleasures of Churchill—good food to eat and champagne, brandy and whiskey to drink. “You can’t make a good speech on iced water,” he once said, and the exploration of his dinners demonstrates that he didn’t believe you could achieve diplomacy without a spirited dinner—the more difficult the mental feat, the longer and more drawn out the dinner. In fact, he often exhausted his opponents as he gained steam throughout long nights. “If only I could dine with Stalin once a week,” he said, “there would be no trouble at all.”

For all his gastronomic loves, he found cocktails distasteful, surprising Roosevelt and his Treasury secretary by enjoying only one of the mint juleps they drafted the secretary’s son to mix for him. He even grabbed a cocktail out of the hands of one of his colleagues and advised her that if she wanted to get drunk, she should “get drunk on something decent.” He was drinking champagne.

“In spite of this, Joe Gilmour, head barman at the Savoy Hotel from 1940 to 1976, is said to have invented the Blenheim cocktail—also known as the four score and 10—in honor of Churchill’s 90th birthday. It consisted of 3 parts brandy, 2 parts yellow Chartreuse, 1 part Lillet, 1 part orange juice, and 1 part Dubonnet.”

This well-researched book shows that the man’s appetites were enormous, that the dinner table can be a stage to set the course of world events and that Churchill’s most formidable appetite may have been his appetite for life.