Table Lessons: The Queen of Creole Cooking Holds Court

Leah Chase stands at the center of a long prep island. The back kitchen at Dooky Chase’s is a windowless space bred for functionwide burners, industrial sinks and metal counters. In contrast, Chase wears a pink baseball cap and an immaculate fuchsia chef’s jacket with her name stitched in white script.

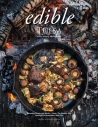

She’s been cooking a fall feast since yesterday, some six to seven courses of wild game: duck, rabbit, Cornish game hen, venison, quail, alligator and what she calls “critter gumbo”—a studded combination of land and seafood that’s as much solid as liquid—as well as sides of diced turnips and cooked greens, wild rice, jalapeño cornbread and puréed sweet potatoes dotted with marshmallows and scooped like ice cream into hollowed orange halves.

Barely visible is the walker that braces Chase’s round hips. At 91, the Queen of Creole Cooking still works full time in the Treme landmark restaurant she’s run since World War II. She vaguely alludes to the day the younger generations of her family will take over the kitchen; it’s unclear if this transition will happen months or years from now or even if she wholly welcomes the idea.

But at the moment, talk is just talk, and Chase still runs the show. Though she is quick to flash her iconic smile, her focus remains as hard as the steel counter in front of her. Right now her concern is plating and presentation.

“Sliced orange. Sliced,” she orders Cleo, her kitchen assistant and niece.

Light-skinned with short hair, Cleo is a tall, substantial women who moves in the narrow lanes with a grace honed by her former years as a basketball player. After working alongside Chase for 30 years, Cleo knows what will be asked for, some 10 seconds before the chef speaks. Cleo is Chase’s right hand woman, now that Chase’s own fingers do not bend as easily they once did.

Cleo holds out more garnish: a sprig of parsley.

“Pinch,” she tells Chase. “Thumb to forefinger.”

“I can’t pinch.”

“Pinch.”

Chase manages to get the garnish between her fingers and tucks it into a meaty crevice. A paper towel holding duck cracklings makes its way around the group, and Cleo’s raised eyebrow says, You want this. There’s no need to chew; the fat melts as soon as it lands on the tongue. Chase uses the rest for lagniappe—golden nuggets flanking the duck.

“I’m always thinking about the details,” Chase tells me. “I wake up and think about food. Now I’m thinking how to plate each of these. Not this one,” she says, pointing at the oval dish on the counter. “Round.”

With each successive display, the hues of fall emerge: ambers, pale oranges and smoky, woody browns. Indeed Chase explains the inspiration for today’s menu comes from a Dooky Chase’s autumn tradition: cooking wild game caught by New Orleans’s first African American mayor, Dutch Morial, and his friends. Over the years, the meals grew from 40 ducks and a small group to three-day endurancecooking events that fed hundreds of men and rivaled a king’s banquet.

“I don’t know how I did it,” Chase says. “And Dutch wouldn’t have paper or plastic. Water glasses. Wine glasses. Cutlery.”

Chase doesn’t let her mind wander for more than a few moments before she’s back on task.

“Give me two cherry tomatoes. I love color. I say if it doesn’t look good, it won’t taste good.”

There is no danger of anything not looking good. As Chase tilts the array of glittering skins for the camera, the loaded plates shake slightly. But Chase doesn’t complain about her joints or cease to smile, revealing teeth as perfect as a row of white corn.

Chase’s staff helps her navigate the walker into the restaurant’s dining room. With the demands of preparation over, Chase settles at the head of table, surrounded by walls painted her favorite red and covered with the explosive colors of her lauded African American art collection.

A plate is put before her, but Chase doesn’t eat. Chase presides. More specifically Chase talks, slipping from one story to the next with the kind of cyclical breathing a jazz singer would envy. She has nine decades of experience to draw from, and it’s obvious she remembers all of them. It’s a ticker-tape mind.

As we eat, Chase manages to cover an astonishing number of subjects: Dutch Morial, Harry Lee, Edwin Edwards.

“I’m a fan of good old-fashioned politicians,” she says. “They knew what they could get away with.”

Kudos also go to Hilary Clinton and Eleanor Roosevelt, whom Chase once heard speak. “She said the only person who can hurt you is yourself!”

Not so much admiration is offered for former Mayor Ray Nagin or anyone from the excuse-maker class. She weaves her way through children. Grandchildren. Great-grandchildren. Cell phones. Spanking. Education. NASA. Art. Work. Rifles. Women.

“Men are born dumb. I’m used to that. But women? I can’t stand a dumb woman. Young women today need to know their power.”

On the subject of “nice stuff,” she grips the arm of her chair and explains that as a young woman she used to covet these very chairs as she passed by the window of a segregated restaurant on her way to work in the French Quarter.

“Of course, I could never have sat in them then,” but for her, the traditional lines and richly colored wood represented elegance itself. Later, when the restaurant closed, she was able to buy the lot for Dooky Chase’s. She smiles, still clearly satisfied that they are hers.

It’s hard not to be overwhelmed by Chase, not because she lords over her accomplishments or her status as a living legend, though she has every right to. Still one can’t help but be aware of her stunning accomplishments and experience. It’s also why it’s tough to write about her; the general tendency is to fill the page with a list of honorary degrees, awards, recognitions and positions that encompass women’s and civil rights, arts and education.

And then there is, of course, the cooking itself. In addition to publishing three cookbooks, Chase has fed two Presidents, the Jackson Five, Jesse Jackson, James Baldwin, Duke Ellington and Ray Charles, among thousands of others. It’s a list that would go to the end of this article. Suffice it to say Chase has fed a significant portion of the significant people in this world.

However, one recent honor allows us a more intimate glimpse of Chase, one that asks us to see not the phenomenon but the fellow mortal. In 2012, Gustave Blache III’s portrait of Chase, “Cutting Squash,” was chosen to hang in the National Portrait Gallery, earning a spot alongside images of this country’s most august citizens.

Blache’s small, realistic painting captures an unposed Chase at work in her prep kitchen. The clearly aged Chef wears a baseball cap and slices a yellow squash. Both the vegetable and the act of chopping couldn’t be more ordinary; still, the canvas suggests complexity, even vulnerability within Chase’s tough exterior. Blache’s portrait, like Chase herself, is a study in contrasts. Her eyes may be fixed on her knife, but the viewer suspects her mind may be in more than one place, remembering something someone said, people she’s known.

We pass plates, slicing and sampling, grateful not to be rushed. Chase’s preparations are not overly fussy and let the flavor of the game come through. While she’s known for her Gumbo Z’Herbes, her Critter Gumbo deserves its own reputation with a savory, rib-sticking taste that may be best described as deep brown goodness.

With fall on the table and tongue, family and food flavor the conversation. While the wild game feasts she cooked for Dutch Morial served as inspiration for today’s meal, Chase reveals that much of what’s on the table goes back much further to her own beginnings. Her father hunted many of the same animals on our table today: duck, venison, rabbit and quail, whose days were numbered the moment they entered the family’s strawberry patch.

Chase explains her mother cooked the birds with government “commodity” butter, one of the free staples her family relied upon. With a limited pantry, her mother, Hortensia Lange, added flavor with stewed plum sauces made from the fruit of the tree that shaded their home. Chase acknowledges she still borrows from her mother’s plum sauces when she cooks wild game.

“This is country food,” she says with obvious satisfaction, and adds she makes a mean squirrel pie.

Chef is now four generations removed from her 1923 birth in the small town of Madisonville, Louisiana. Her parents had elementary-level educations; Jim Crow–era segregation prevented more and while they were determined their daughter would finish high school, circumstances required that Chase knew work and responsibility from a very young age. Her eldest sister died as a toddler from a tragic burn accident; as a result, Chase was raised as the oldest of 12 girls. (Her parents eventually had two sons.)

As a young girl, Leah and her sisters rose at 4am to walk to the strawberry fields three miles away, work for a few hours, then walk back and head to school.

“I grew up hard, I guess,” she says.

But what Chase shares is not a litany of difficulties or even injustices. Indeed what she seems to emphasize is not what lacked but what received: steadfast and powerful lessons about work, morality and family, lessons often imparted around food. For instance, Chase believes she was given something that most city kids won’t ever know—a connection to the natural world, the changing of the seasons, the names of trees and a knowledge of “which plants you could pick, which ones you couldn’t.”

For some, farm to table may seem like a recent hot trend; for Chase, it was a way of life born from necessity. In addition to what her father hunted, the family vegetable garden helped to fill the plate. She smiles as she tells us how her mother once sent her out to pick wild purslane when they had run out of greens in their garden. Young Leah was to be secret about it.

“She was proud,” Chase says of her mother, “and didn’t want anyone to know we were so poor we had to eat weeds.”

Decades later, Chase sat down to dinner in an upscale California restaurant only to open the menu and find purslane named among the pricey appetizers.

“We always came to table,” Chase says of her childhood meals. Mondays through Saturdays, the table was laid with practical oil cloth; but come Sunday, this Catholic family sat at a table dressed with good dishes and a pressed tablecloth her mother sewed from flour sacks. It was from her mother that Chase learned what she calls “an appreciation for the finer things,” an aesthetic she would bring to her own white-linen restaurant.

Chase says she has always believed in the power of beauty to inspire individuals to strive for better circumstances. Her mother also trained her daughter to be aware of appearances, especially in the face of guests. It’s an attitude Chase has retained with her own staff who are instructed that customers are to be treated “like company.”

When she expresses concern for children who grow up eating a corner store stock in front of a television, it’s clear that, for Chase, her family table offered more than food or future recipes. Indeed food, as important as it is to her, is not what she most speaks about. What she most speaks about is people.

As a girl, she learned an important connection between meals and humanity: The table was a place to build consensus, not opposition. Her parents would not tolerate arguments and infractions were met with the razor strop.

Years later, amid the full tensions of the civil rights era, Chase would use the upstairs dining room of Dooky Chase’s to build the boldest sort of consensus of the day. Defying segregation laws, Chase used her tables as a meeting point between black and white.

Of all seasons, autumn’s food is most about memory. As the leaves turn and the days shorten, we find ourselves craving hearty fare and local ingredients, longing for family recipes and traditions of exactly the kind Chase has served in full today. And so I ask Chase, herself a tradition and now deep into the autumn of her own life, if there are particular foods that continue to compel and resonate with her emotionally.

“Oh, yes,” she replies without hesitation. “Gumbo, stuffed mirliton and peppers.”

Her loyalty to what she calls the cuisine of Creoles of color clearly runs deep on the Dooky Chase’s menu. She says she’s proud to have run a restaurant where patrons can sample authentic preparations after they’ve tried “the other Creole” restaurants like Commander’s Palace and Galatoire’s.

“Go back to what you know,” she advises. “Go back to what you know.”

After 91 years, what Leah Chase knows is more than most of us ever will. Outside the kitchen, Chase is known as a staunch advocate for social progress, but today she’s been a model of another era and its table lessons. And if there is a commonality between those lessons, it’s dignity: the dignity of the land, of good food, of the table, of fine things, of choice and, above all, of work and action.

What comes through Leah Chase the talker is Leah Chase the worker. Such lasting values explain why, when others would have considered retiring 30 years ago and simply let the accolades roll in, Chase continues to rise early to come to Dooky Chase’s.

“I wasn’t raised on kisses and hugs,” Chase says. “We kissed twice a year. Christmas and New Year’s.” She admits she could be more generous with her shows of affection. In the several hours we’ve spent talking, it’s the closest she’s come to voicing regret. “But we did learn that family was there for you. No matter what.”

“You see, I have to be able to do this for people,” she says, pointing to the dishes between us. After some two hours at table, the birds have been picked over, and the gumbo bowls sit empty. She instructs her staff to bring out the peach cobbler, a final country food finish. The sliced fruit and crumbles are neither too tart or sweet.

“I do. That is who I am,” Chase proclaims. “This is how I show my love.”