Sh-Sh-Sh Sherry Bomb!

Raise a pinky to the resurgence of sherry

For many, the image of a sherry drinker might conjure a ruddy-cheeked Falstaff with a cup of “sherris sack,” or a tweedy professor enjoying a nip with afternoon tea. But sherry is shedding its dusty rep. Today, you’ll find sherry wine cropping up in sexy cocktails, taking center stage on restaurant beverage lists and occupying unprecedented retail shelf space.

That’s welcome news for devotees like Derek Brown, whose passion for the stuff led him to open the sherry bar Mockingbird Hill in Washington, DC, in 2013. This establishment, and others springing up in the world’s most cosmopolitan cities, have helped a new generation embrace a tradition that saw its last heyday in 17th century Europe.

“I feel like the rise of sherry is a long time coming but also something that already existed in the world,” says Brown. “It’s not new—it’s just new again.”

Barrels of fun

Sherry is a fortified wine produced in the Jerez region of southwest Spain, in an area commonly referred to as the Sherry Triangle, bounded by the towns of Jerez de la Frontera, Sanlúcar de Barrameda and El Puerto de Santa Maria. Its distinctive solera method of production involves fractional blending, or introducing younger wines into older wines at various intervals to give each vintage a unique character and taste.

Three main grape varietals are used to make sherry: Palomino, Moscatel and Pedro Ximénez. While sherry is commonly thought of as sweet, most sherries are in fact quite dry. But sherries run the style gamut—from dry Fino, briny Manzanilla and nutty Amontillado to rich Oloroso and sweet Pedro Ximénez (PX for short), as well as the distinctive Palo Cortado.

Some varieties, like Fino, are aged under flor, a yeast-like growth that prevents oxidation and helps the wine maintain its dry, crisp character. Sherries whose aging process includes partial or no flor, like Olorosos, develop a richness or roundness that distinguishes them from their drier counterparts. And each producer employs his or her own methods—medieval and modern—to create a variety of sherries that is extraordinarily broad and complex.

The wide world of sherry

The turning point for Brown came when he tried an Adonis cocktail—a blend of sherry, vermouth and Angostura bitters—at Citronelle in Washington, DC. “It was dry, not sweet, and goddamned delicious.” That discovery sent him “down the rabbit hole: chasing cocktails, learning styles, going to Spain multiple times … It’s like a song that gets stuck in your head, and I couldn’t stop humming it.”

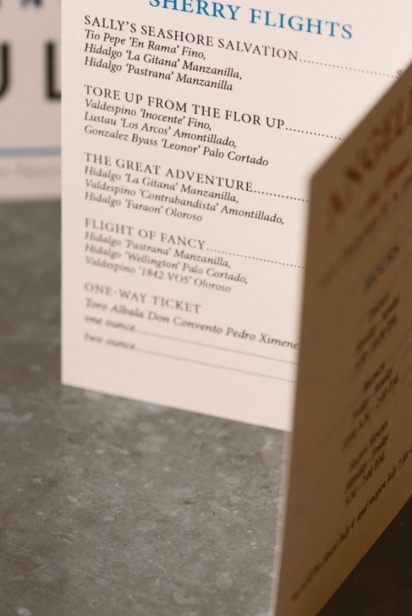

Christine Jeanine Nielsen, the lead bartender at Angeline in New Orleans, first encountered sherry during her tenure at New Orleans’ (now closed) Lucky Rooster. She carried that expertise with her to Angeline, where sherry occupies its own section on the front page of the beverage list. “When Angeline first opened, our sherry list was larger than our reds and whites by the glass combined, and a lot of people thought that was crazy, but it worked,” says Nielsen. “I sell sherry flights and sherry by the glass every night that I work.”

As with many food and beverage trends, devotees within the service industry have fanned sherry’s flame, with bartenders becoming excited, then servers, then “regulars” who spread the word. “At this point in New Orleans, it’s kind of across the board: All sorts of people are interested in sherry,” says Nielsen.

According to John Keife and Jim Yonkus of local wine and specialty foods retailer Keife & Co., consumers are eager to bring the sherry experience home as well. In addition to clientele from the service industry and a hearty base of millennials, they are selling sherry to people who are “well-traveled, who have been to Spain” and are surprised to see some of their favorite bottles available on local shelves.

Distributors have broadened their offerings, says Keife, because they are passionate about the product. “They realize it was underrepresented and underappreciated. More are believing it’s going to sell and making that stand. There is this opening, an opportunity to buy stuff that wasn’t there five or 10 years ago,” says Keife.

That’s true for Mockingbird Hill as well. “We’ve had a hundred sherries on our list at some points,” says Brown. “That’s a lot of sherries. And we could have easily added another hundred.”

A guiding hand

People who expect to find sherry only among a restaurant’s dessert wines are often surprised to learn that sherry can be consumed like other wines: before, during and after a meal, and with all kinds of food. When Nielsen helps the uninitiated navigate the sherry list, she will typically present them with a Fino or Manzanilla, an Amontillado and an Oloroso. “Those are the three styles that bring people in. Sometimes I’ll suggest they have a PX, something a little bit sweeter.”

At Keife & Co., Keife starts by finding out what a customer typically drinks—red or white. “It’s rather general, but I would say if you’re exclusively a white drinker, maybe the Fino is a little drier. Stylistically it’s going to be leaner, higher acid, and I lean more towards Fino in general because you drink it slightly chilled. It’s a good aperitif. But if people lean toward either lower tannin or sweeter, I would recommend Oloroso or something that is a little richer in style.”

“There’s no wrong answer,” adds Yonkus. “If you’re doing a dessert, you might want the PX or something that’s going to be sweet and rich and hold up to that intense dessert.”

Mixologists give sherry a shot

While demand for sherries by the glass continues to grow, bartenders are also showcasing sherry in innovative cocktails. “The creativity and range of usage of sherry in cocktails is unprecedented,” says Brown. “Just Google ‘sherry cocktail’—you’ll spend a week lost in the internet.”

There is even a U.S. Sherry Cocktail Competition—Nielsen was a finalist in the 2015 contest held at the Clover Club in Brooklyn, where she served her “The Right Side of Jackson” (below).

Cocktails not only display sherry’s versatility, but they can also help entice wary drinkers. “It takes down some of the barriers of being intimidated by the traditional simple, single fortified wine,” says Yonkus.

The case for sherry

Even the most ardent fans admit sherry can be an acquired taste. “Not everybody likes sherry off the bat,” says Brown, “but we’re talking about a large group of wines ranging from the driest in the world to the sweetest in the world. They are full of complexity. It’s hard for me when people just outright reject sherry having only tried one or two, without understanding the deep well that they’re drinking from.”

Sherry boosters are quick to rattle off its many positive attributes. For starters, “It’s inexpensive and high quality,” says Yonkus. “There are some more complex things that get up there in price, but your basic Fino for 750 ml of something top grade is 20 bucks. And it’s awesome.”

Because it’s fortified, sherry also lasts longer than conventional wines once it’s been opened. If capped and refrigerated, it can last close to a month—even longer for the sweeter varieties. Many sherries are also available in half bottles, so there’s a good chance they won’t make it to the fridge at all.

An added bonus? Sherry won’t derail your diet. Nielsen calls dry sherries “the ‘OG’ skinny wine.” She even drank it during a weight-loss competition among friends. Rather than giving up alcohol altogether, she opted to continue drinking just sherry. “That flor eats up all that sugar in the barrel,” says Nielsen. And she won the competition.

The Right Side of Jackson

Currently on the menu at Angeline, this cocktail was a finalist in the 2015 U.S. Sherry Cocktail Competition.

1½ ounces Tio Pepe En Rama Sherry

¾ ounce Grand Marnier Rouge

½ ounce Tempus Fugit Creme de Menthe Liqueur

Pour ingredients over ice and stir. Strain into a chilled snifter.