The Regulars: Neighborhood Bars and Why They Matter to New Orleans

In his evocative, heartfelt Katrina memoir, A Season of Night, local food critic Ian McNulty writes of a pivotal emotional moment in November 2005, less than three months after the storm. While out with his dog during their routine evening walk, McNulty came across a dim flicker in his otherwise still blacked-out section of Mid-City.

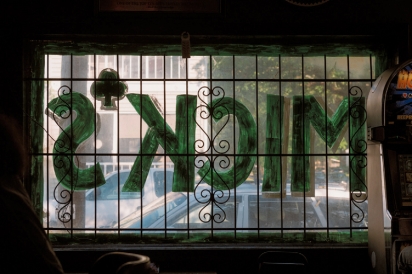

Moving closer, he found the Banks Street Bar, a corner pub, had re-opened with only a cooler of ice, a radio and a few candles. People, mostly men, had gathered inside the moonlit, moldy walls, pulling stools around a flood-wrecked pool table. “... it seemed like a miracle,” McNulty writes of hearing the din of voices and seeing the shadowy figures inside. “Instantly, the bar had resumed its role as a neighborhood gathering place.”

Indeed, the Banks Street Bar was the first business McNulty witnessed reopen in his area. “In the months that followed,” McNulty would later conclude, “through all the darkness and fear, the best moments of encouragement and happiness came more often from bars and restaurants than anywhere else. They ... were the fires around which we circled for reminders of the city’s life and culture before the storm, for company and sometimes literally for warmth.”

We are a city of drinkers, albeit at times to excess. A city of strolling drinkers, of roaming drinkers, of dog walking drinkers, of festival and parade drinkers, of lazy day in the park drinkers, of porch and balcony and courtyard drinkers, of morning and happy hour and late night drinkers, of occasional drinkers, of daily drinkers, of pocket flask drinkers, of costumed and wigged drinkers, of marathon-running and bowling drinkers, of drive-thru drinkers, of bicycling drinkers, of horse- and rickshaw-riding drinkers.

More than anything else, we are among the last holdouts of a vanishing breed in America: a city of neighborly drinkers.

A couple of years ago, my co-authors Elizabeth Pearce and Richard Read and I wrote The French Quarter Drinking Companion, an anecdotal guide to 100 bars in America’s most eccentric neighborhood. Even before our first round, we understood that drinking in the Vieux Carré would prove a decidedly different beast. And not just because there were so many bars (far more than 100 packed into less than one square mile) or because of our right to meander with a 42-ounce daiquiri in hand. These were just the overt signs of something less tangible and more important we came to see about the longstanding spaces, both physical and psychic, drinking occupies in New Orleans.

Eventually we came to articulate what we’d instinctively known all along: Bars here are about a lot more than just getting blotto. Certainly there are those establishments, as well as those meant to impress or those where the patrons sip to jazz standards or those where they down day-glo shots before belting out the words to Journey’s “Don’t Stop Believin’”. However, even among the roving conventioneers and tiara-wearing bachelorettes, we found that off-the-beaten-track hangouts not only exist but thrive.

We came to remember that although only a small number of this city’s population lives in the Quarter full-time, others spend the bulk of their days or nights working there. In others words, some 300 years after its founding, the Quarter remains foremost a neighborhood. It remains our city’s foremost neighborhood. And ultimately, it was the bars with a steadfast and loyal clientele of the likes of Erin Rose, Fahy’s or the Golden Lantern, where we most liked to imagine our Vieux Carré doppelgangers sitting on their regular stools come 6 o’clock.

In New Orleans, neighborhoods don’t exist in spite of bars but in conjunction with them, and in some cases, owe much of their identity to them. For locals or long-time residents, this statement may be obvious. However, it’s important to remind ourselves that our fondness for these neighborhood spots doesn’t exist many other places, if anywhere in the United States, to the same extent. In fact, most cities prohibit bars in the center of neighborhoods. Seen as social threats or tolerated vices, bars are often relegated to heavily commercialized streets or the flinty edges of towns and sometimes (Handkerchiefs, please) outlawed entirely.

The term “neighborhood bar” may sound easy enough to define, but start that conversation and you’ll quickly see how many factors come into play. Neighborhood bars generally serve those who live or work within walking distance. They aren’t about pricey craft cocktails, and show-offs can expect more stink eye with their orders than accuracy. While there may be food, drinking takes top priority.

There’s also the issue of price: The bar must be reasonable enough to develop a regular clientele that can routinely afford a couple of rounds.

Unlike restaurants, neighborhood bars don’t come with high price tags or time pressures to clear out with the check. Live music may also happen, but a jukebox or satellite is more likely and if bands appear, they come later, after gossiping or the paper or the game. Another feature of a good neighborhood bar is its tolerance of difference, spots equally welcoming to the sensitive soul reading poetry as well as the six-man road crew clanking bottles. Here lapsed friends can take their time catching up or the solitary drinker can find enough chat to avoid loneliness.

“If you go to other cities, they don’t have a collection of neighborhood bars like we do,” says Rhiannon Enlil. A bartender for the last 15 years, five in her current position at Erin Rose in the French Quarter, Enlil has had ample opportunity to consider the lure of neighborhood bars and why they continue in such numbers in New Orleans.

Enlil points to Pal’s in Bayou Saint John as the classic example of a neighborhood bar: smallish with an architecturally appropriate footprint, independently owned, nestled by homes and frequented by those who live nearby. But she’s also quick to point out that neighborhood bars aren’t defined exclusively by location.

“A neighborhood bar is less about placement than about certain qualities,” she contends. She tells the story of how in the days following the evacuation for Hurricane Gustav, Molly’s on the Market remained open, offering a haven from the otherwise shuttered fronts and empty streets of the French Quarter. The usually heavily touristed Decatur Street spot became a defacto neighborhood bar where locals like Enlil could gather, sharing news and drawing comfort from numbers, all for the cost of a cheap drink.

“A good neighborhood bar is about investment, both by the owners and the customers,” Enlil notes. “It’s about being grounded in that space. They aren’t brands or chains. They offer singularity. Ultimately, it’s atmosphere and conversation that are most defining.”

These qualities may explain why the Erin Rose, despite being just steps from the eternal lug and slug of Bourbon Street, still feels as deeply rooted as other establishments on tree-lined streets. Enlil says her customers, both locals and tourists, are moved by the intimacy and one-of-a-kind authenticity they find at the Erin Rose. “They say, ‘People talk to me here.’ It’s a part of why people want to return to the bar and the city. Other places, it’s all so factory made.”

“What’s true about neighborhood bars in New Orleans was true for many cities before Prohibition,” says Elizabeth Pearce, a cocktail historian and owner of the popular Drink and Learn walking tours of the French Quarter. “Saloons, bars, taverns, beer gardens were once all cornerstones of neighborhood, political and even family life. What’s different about us is that we never followed the rest of the country in seeing drinking as sordid or seedy. You don’t allow activities that you see as dirty into the center of your neighborhoods.”

Rather, Pearce adds, drinking has always been considered an extension of our culture’s celebratory nature. “It’s the oil of conversation. A neighborhood bar helps fulfill that function.” She also points to certain historical facts that have contributed to our embracing of neighborhood drinking spots, including the city’s dominant Catholic (never Puritan) population. There’s also the fact that during Prohibition, more alcohol flowed through these ports than any other, prompting the Feds to dub New Orleans “the wettest city in America.”

But Pearce is quick to point out that not all neighborhood bars that like to call themselves such are worthy of the moniker.

“A neighborhood bar isn’t a dive and it’s not fetishized, high-end mixology scene. It has to be affordable,” she says and points to Markey’s, a few blocks from her home in the Bywater, as an example of a genuinely neighbourhood-driven spot. Enlil agrees. Despite the enormous positive exposure and prestige that came with working the craft cocktail scene at Cure on Freret Street, she ultimately chose to return to Erin Rose. “The social interaction began to take priority,” she explains. “I tend to care less about the meticulousness of the drinks than the dynamic of the room.”

Indeed, too upscale and a bar runs the risk of becoming the cocktail equivalent of a gated community, leaving most of us standing outside the fence. It’s a concern heard more frequently of late. Rising rents and a flux of fairly wealthy transplants mean that most newly opened bars, even those dubbing themselves as neighborhood spots, have noticeably higher prices. While most cocktail enthusiasts and bartenders I’ve interviewed are thrilled by the chance to offer quality and rare ingredients, many on the stools long for the days of $3 wells. As a longtime local bluntly told me at the mention of a newish bar in the Marigny, “I can’t go there. I can’t afford to spend $50 just to get a little drunk.”

“From a selling or buying standpoint, a good neighborhood bar isn’t just a convenience but a feature,” says Jean- Paul Villere, longtime New Orleans resident and owner of Villere Realty. As a successful real estate broker, Villere is well aware of how a nearby drinking spot can affect property value. “There are plenty of places in this country where walking to a bar is frowned upon. But unlike a lot of communities, bars here are woven into the fabrics of our neighborhoods. Practically speaking, people don’t want to have to get into their cars to drink.”

However, Villere also notes that not all bars, even those we might assume are neighborhood bars, inspire community. He points to the 1700 block of Washington Avenue in Central City as a case study. Before being relaunched by Powell Miller as Verret’s Lounge last year, the building housed a bar called The Turning Point. The Turning Point was known for its motto, “Where the mature crowd comes.” Having worked with clients purchasing homes in the immediate area, Villere notes the former bar catered specifically to older African-American males and was “unwelcoming” to others. However since the bar has changed hands, uncovering some of its original architecture and dubbing itself “freak-friendly and hipster-tolerant” and installing a back patio complete with grills available to their patrons at no cost, Verret’s has spawned foot traffic, drawing a decidedly more diverse crowd, while maintaining affordable drink prices and many of the original patrons.

Villere has had other clients purchase homes in the area; one recently chose to hold a birthday party at the lounge. It’s these kinds of social interactions, Villere says, that help keep neighborhoods vibrant, solidifying connections between existing residents and drawing new interest. “Verret’s is now that. It’s the kind of place that isn’t a cop bar or a lawyer bar, but where I wouldn’t be surprised to see either.”

“A good neighborhood bar should offer a mix of race, class and age,” he says. And while that statement should be self-evident, the reality is that far too much division still exists in New Orleans, even within neighborhoods. A great local bar can help to overcome those perceived barriers.

Ask a local her favorite neighborhood bar and chances are it won’t be long before someone says Finn McCool’s. Opened in July 2002 by veteran bartenders Stephen and Pauline Patterson, Finn’s brought attention and traffic to Banks Street long before it became the popular location it is now. Despite opening in what Stephen describes as a then “rough” section of Mid-City, the Pattersons were determined to create something their neighbors would feel proud to come to. “We didn’t want to be just another watering hole,” says Stephen.

While wanting their bar to reflect a relaxed New Orleans style, the Belfast natives also drew from Ireland’s pub traditions. “The pubs we grew up with functioned as community centers. They were where you went at the end of the work day,” says Pauline. She notes that while the Irish have been long stereotyped as excessive drinkers, moderation generally reigned; alcohol served as the precursor to other social functions. “Pubs were more about catching up, gossiping or job-finding. They were a place to unwind between work and home. We wanted to re-create that part of home in New Orleans.”

But it’s one thing to say that you want to create community and another to actually make it happen. And given the neighborhood’s scruffy reputation, the couple knew that they would have to work very hard if they wanted customers to feel invested enough to return. It may seem difficult to believe given Finn’s chronic numbers now, but in its first years, the crowds were considerably thinner. Stephen and Pauline worked seven days a week, making a point to shake hands, learn names and introduce customers to one another. Pauline went so far as to ask strangers to sit closer, bridging empty stools in order that strangers might talk. Not everyone responded to that kind of push but most did.

“Activities,” Pauline adds, holding up her finger. “Give people an activity and they have no choice to interact.” Darts. Pool. Soccer games all weekend. Trivia night. Rec league soccer teams.

Before the storm, the Pattersons note that the focus of Finn’s was on them. However, a shift happened in the wake of Katrina when customers and neighbors rallied around the pub, helping to gut and rebuild the bar, using Finn’s as ground central for sharing news, resources and spreading word of displaced friends. Perhaps most important of all was how the bar’s rebuilding became a litmus for the area’s recovery. Multiple locals with flooded homes approached the couple about their plans, explaining that if the pub was willing to wager on rebuilding, they would too. (Award-winning writer Stephen Rea’s memoir Football: The Birth, Death, and Resurrection of a Pub Soccer Team in the City of the Dead offers another angle on how Finn’s helped its customers come back after Katrina.)

Now, nearly 10 years after the storm, the pub shows no signs of slowing down, as it continues to sponsor kickball teams and fundraisers, like Saint Baldrick’s. Recently an extraordinary 162 Finn’s customers, including Pauline herself, shaved off their hair in honor of the fabricated saint and in the process, raised over a $100,000 dollars for cancer research. Pauline notes that the focus of the bar is no longer on its owners but a dedicated customer base who see Finn’s not only as a sports bar or as a funky pub, but as a cornerstone of community.)

The couple hopes to keep that sort of social and emotional investment with its second venture, Treo on Tulane. Whereas sports dominate the screens of Finn’s, Treo has no televisions whatsoever and centers on the arts. It’s a decidedly tonier space with sleek grey walls and decidedly sophisticated fittings. “Treo is the Irish word for ‘direction,’” explains Pauline, who wanted to see her newer establishment, as well as Tulane Avenue itself, head in a different direction.

And while Treo may be a bit too upscale to qualify as a neighborhood bar, it still holds true to the ideas of community. For instance, the couple made efforts to hire Finn customers whenever possible for Treo’s build out, including the creation of an eye-catching ceiling map of the city from repurposed wood and materials. Upstairs, Pauline’s passion for art and activities continues with a poster advertising pet adoptions and a gallery currently showcasing works by New Orleans lawyers and police officers (with a portion of proceeds benefitting charity). The night I interviewed Stephen and Pauline, a small group had gathered around easels, chatting and awaiting the start of a painting class. Other nights the space plays host to a creative writing course taught by Stephen Rea.

Treo is now home to so many events that Pauline needs to pull out her phone in order to keep track of the weekly rundown. “People think that it’s all us doing all these things,” she says as she scrolls down the calendar. “‘How can you do all this?’ they ask. But it’s not just us. It’s the customers.”

“In placemaking, it’s not just about the place,” says Emily Talen, author and professor of urban planning at Arizona State University. “Sometimes the making part is more important than the place itself.”

In New Orleans neighborhood bars continue to “make” place by creating community. Despite living in a time when so much of our interaction now happens online, our neighborhood bars offer what Facebook or Twitter can’t: physical contact. Affordable and tolerant, our local drinking spots have become synonymous with the friendly banter our city is known for. As Stephen Patterson puts it, “Where else can you go, and for two dollars, make a new friend?”

When asked why New Orleans’ neighborhood bars continue to thrive with such force, Rhiannon Enlil says the answer comes down to our human need for connection. “People want to cluster together in a place that feels like home.” It’s a feeling that extends to both sides of the bar. “I’m helping to run a household,” Enlil says. “I’m a facilitator, watching connections be built before my eyes. When a neighborhood bar is wellrun, that’s what happens. They become friendly. They become magical.”