Alan Walter, Head Bartender of Loa on Things Old, New, Borrowed and Booze

Alan Walter, head bartender at Loa in the International Hotel, is almost indescribable and, without a doubt, as multifaceted as New Orleans herself. Mining his past to inform his present, he provides experiences at the bar that reflect his youthful passions for scouring flea markets with his mother and methodically excavating at the property line of his backyard for buried treasures, as any aspiring paleontologist would.

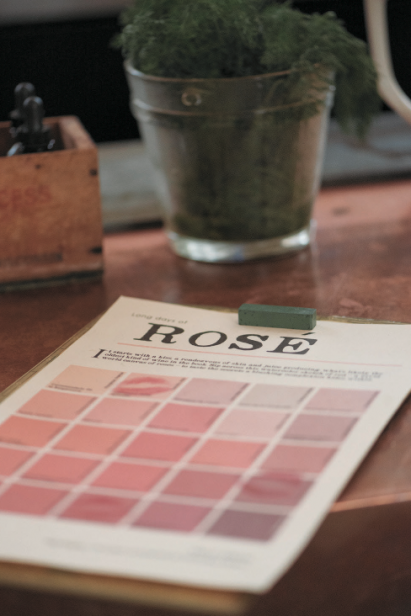

Walter’s passion for all things old— like the Underwood typewriters he still uses, the “grandma glasses” in which he serves his drinks and the ’65 Pontiac Bonneville he drives—aren’t an affectation, but rather an appreciation of what formed him and what his locale provides to inform his nightly menu.

“I’m definitely some sort of dinosaur or something,” says Walter.

“I have 3,000 country albums. I accidentally had a great first car: a ’67 bright yellow convertible my parents were getting rid of that I begged to have. Early on I was smitten by muscle cars and it wasn’t because I was retro. I always loved the older ways and older things.

“I’ve always driven old American cars. Now it is a blue Pontiac Bonneville ’65—huge engine, skirts in the back. It’s a great connector. It’s always had me meeting a generation of older mechanics. And all the people who were conceived in one or had one in high school,” he muses.

“When you are creating things you are going to be mining. You don’t just work with ideas, you work with physical realities and appearances and one of the closest places you’re going to explore is your past.”

Take for instance his vintage glassware collection and other vessels he uses for his drinks. His collection is expansive, as you’d expect from someone who has been stockpiling them for decades. He explains, “You can’t ignore that the vessel you’re drinking out of makes a big difference. I have been a thrifter and flea market junkie with my mom since I was 8, so I have a head start on finding a steady supply of antique glassware. Sometimes flea market dealers will even hold things for me.

“There’s always a new opportunity for repurposing things, too, like those milk-white bud vases which used to sit on the thrift store shelf for a $1. Suddenly they got collectable and now I am using them for a tiki-style drink for a summer event. I’ll freeze it, top it with a metal straw, and a sprig of bamboo and now it is a modern tiki drink. But I didn’t look at them that way even a year ago. It makes for a cool drink, not being able to see what you’re drinking, really.”

He treats ingredients the same way he treats his found objects. There’s no missing the lineup of local herbs filling the bar that and leaving the air redolent as the bartenders cut into those that Walter has foraged or neighbors have kindly dropped by. Guests are able to wrap their arms around the city by experiencing the locally foraged ingredients Walter injects into his recipes.

“There’s something about eating or drinking, something that is physical and sacramental—it is different from picking up the souvenir in a souvenir store. You’re embracing it to the point of putting it in your body. That’s pretty fun. There are plenty of questions about where these things come from and there’s just enough story for people to have some excitement about the fact that they are here.”

A dedication to “being here” is evident in the way that Walter brings terroir to his menu, with nothing being too inconsequential, whether it is clover flowers cut from an empty yard or lotus growing in a swamp an hour’s drive from the bar.

He rejects the label of forager, saying, “The reason I might not consider myself a forager is that I am not always after the extremely rare item that some may think the term might imply. I use things that are so plentiful that that they are considered valueless on some level—like bamboo and pine needles; these are things people want cut out of their yards, pretty much. They don’t have value in that way that certain other items do.”

For Walter, it isn’t about a fascination with strange combinations. He says he is guided by nothing more than “the desire to serve, to present [New Orleans] in a way that can be consumed. A good dish or cocktail should just perplex the palate, put you in a zone that’s a little out of balance, and hold the familiar in one hand and the new in the other.”

There is a long history behind sourcing local ingredients and bringing locale to life at a bar.

“The French will use everything on the local countryside. A liqueur has to do this. You have to kind of feel a complexity of things all at once. These liqueurs that do that are fascinating to me—they can have 40 or more ingredients. I’ll probably be making something like that out of our local stuff eventually but the drinks are a small format for doing that—connecting locals, locale and tourists.”

An acceptance of drinks with ingredients made from ingredients you’d never expect to see in a glass are Walter’s forte. And fitting for the bar and the city in which it lives and breathes, a city Walter sees as having a special way about it that the past still bleeds into the present.