A History of Réveillon

“Christmas was ushered in as usual, with the tolling of bells, the firing of guns, the sputter of (fire)crackers, the throng of the market ... Never did we experience a more invigorating morning than that of 1837, giving zest to the eggnog which prevailed at different firesides,” reported The Picayune (a predecessor of The Times-Picayune) in 1837, the first year of the paper’s existence.

However, the New Orleans Creole population likely tried to ignore this type of rowdy celebration and saved their excesses for New Year’s Day, when high spirits were more acceptable to their strict religious and moral standards.

“Church bells called the faithful to the midnight mass service … For Creole New Orleans, this was the only place to be on Christmas Eve,” according to Harnett Kane in The Southern Christmas Book. Anecdotal information passed down over the years reveals the nonchalant attitude of Creole men toward church attendance, and Kane mentions this as well:

“A man might miss almost any service in the year, but he would feel deep regret if he did not join the women for the solemnities of the holy night.” (Whether the men feared for their souls or the wrath of their scrupulously religious wives is unknown.)

Christmas for the members of this devout group reflected their solemn attitude toward much of the holiday season. During Advent, the four weeks before Christmas, many Creoles abandoned the opera house, theaters and other festivities to focus on quiet reflection and prayer. Unlike Americans, Creoles did not exchange presents on Christmas. Instead, Pere Noel visited the children to fill their stockings with a small gift, fruit and candy. On Christmas morning, in keeping with their religious beliefs, French Catholics observed the day with their usual holiday decorum, perhaps another mass; then parents took their children to several different churches to view the crèche scenes on display. Christmas Eve was a day of strict fasting.

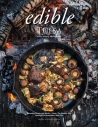

The Creoles ended their midnight worship and fast with a réveillon breakfast, a modest meal compared to the usual family meal or dinner party. The dining room of a prosperous Creole family would have been inviting with delicious aromas and a blazing fire in the marble fireplace. Candles would have flickered over the bounteous table, and the “modest” meal would have included three courses comprised of items such as daube glace (a jellied and spiced meat), various egg dishes, oysters, gumbo and grillades (medallions of meat, often veal, simmered in gravy). A rich cake filled with jelly and covered with cream was the customary dessert.

Although the drinking at a réveillon meal was lighter than usual, wines were served. There are several liqueurs that would have been acceptable at this time when heavy drinking was inappropriate. The “old aunts” in 19th-century French Quarter families often made their own special brand of anisette for holiday guests, according to Leonard Huber, author of Creole Collage. Homemade cherry bounce and the ever-popular eggnog were also innocuous favorites on this night.

The word “réveillon” (from réveiler, to awaken) was originally used in France hundreds of years ago to describe this early breakfast following midnight mass on Christmas Eve. This tradition, nearly always in a private home, continued in Louisiana. After a cold December night, the réveillon meal served to warm and enliven not only the adults, but the older children who were allowed to join them at church. It was an honor for someone outside the family to be invited for the réveillon meal, which was usually restricted to only the closest friends.

By mid-19th century, with the large influx of Americans plus changing customs, réveillon became less popular; later on in the century many families began to celebrate réveillon in restaurants instead of at home. (Christmas in New Orleans by Peggy Scott Laborde and John Magill) By the 1930s, réveillon was just about forgotten.

And yet New Orleans has a way of recalling the past.

In 1988 French Quarter Festivals, Inc. (FQFI), a nonprofit organization supported by the city of New Orleans, recommended that local restaurants bring back réveillon dinners as part of marketing the Quarter to locals according to Jyl C. Benson in New Orleans Magazine. New Orleanians quickly took to the idea and several restaurants began to serve réveillon dinners. Originally, these restaurants, in agreement with the FQFI, were required to serve the traditional réveillon dishes. Later on this became a problem for inventive New Orleans chefs. This traditional approach has been relaxed and chefs can be creative in their approaches to the meal. Some chefs enjoy returning to strictly traditional Creole dishes for the dinners, while others are more playful with the menu. Café Adelaide features a chargrilled oyster

stew, for example.

Réveillon has changed a great deal since the first half of the 19th century when it was widely celebrated by the Creoles in the Vieux Carre. It’s not as closely associated with midnight mass (it is now served nightly from throughout December); it has become much more lavish; it’s shared with friends as well as family; and it’s generally served at restaurants and not so much at private homes. It has, however, remained somehow the same. It is part of the spirit of sharing and love for friends and family that we express mostly at Christmas.

Check out FQFI.org to find one of the 45 New Orleans restaurants in six neighborhoods that serve these fixed-price multi-course réveillon dinners starting at $34 from December 1 to 31.